RA ch12 Autocorrelation in time series data

Ch 12: Autocorrelation in time series data

In the previous chapters, errors \(\epsilon_i\)’s are assumed to be

- uncorrelated random variables or

- independent normal random variables.

However, in business and economics, time series data often fail to satisfy above assumption. In time series data, error terms are likely to be autocorrelated / serially correlated over time. Is is mainly because

- one or more important predictor variables are missing (when time-ordered effects of certain variables are positively correlated, so do error terms in the regression model. The error terms would include effects of missing variables.)

- there are systematic coverage errors in the response variable.

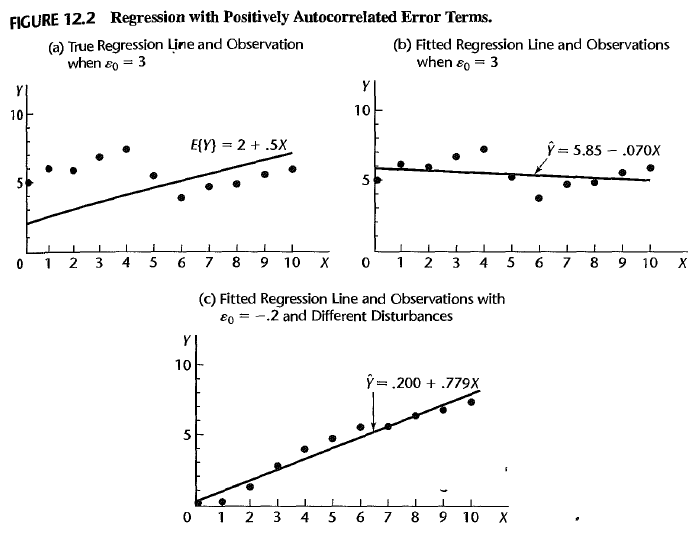

Autocorrelation or positively autocorrelated error terms may trigger problems such as:

- \(E(b) = \beta\) but \(Var(b)\) is not the minimum

- [\(MSE\) / \(s(b_k)\) ] may seriously underestimate [\(\sigma^2\) / \(\sigma(b_k)\)] \(\Rightarrow\) confidence intervals and tests are no longer applicable.

- the regression line sharply differs from the true line

- the regression line is sensitive to the initial error \(\epsilon_0\)

Therefore, we need to analyze a regression model with autoregressive errors, test if a model is autocorrelated and then remedy autocorrelation.

Outline

-

First order autoregressive error model

- One predictor variable case

- properties of error terms

- Durbin-Watson test for autocorrelation

- Remedial measures for autocorrelation

- addition of predictor variables

- use of transformed variables

- way 1: Cochrane-Orcutt procedure

- way 2: Hildreth-Lu procedure

- way 3: first difference procedure

- forecasting with autocorrelated error terms

1. First order autoregressive error model

one predictor variable case

The generalized simple linear regression model for one predictor variable when the random error terms follow a first order autoregressive, or AR(1), process is

1: \(Y_t = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_t + \epsilon_t\)

2: \(\epsilon_t = \rho \epsilon_{t-1} + u_t\)

where \(\rho\) is a parameter such that \(|\rho| <1\) and \(u_t\) are independent \(N(0, \sigma^2)\). \(\rho\) is called the autocorrelation parameter.

Above one variable case can be generalized to multiple variables case. The only thing changed is the first line 1’: \(Y_t = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{t1} + \cdots + \beta_{p-1} X_{t,p-1} +\epsilon_t\).

Remark When it comes to a second-order process, the line 2 is changed to 2’: \(\epsilon_t = \rho_1 \epsilon_{t-1} + \rho_2 \epsilon_{t-2} + u_t\).

properties of error terms

- \[E(\epsilon_t) = 0\]

- \[\sigma^2(\epsilon_t) = \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2}\]

- \[\sigma(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1}) = \rho \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2}\]

- \[\sigma(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-s}) = \rho^s \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2}\]

- \[\rho(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1}) = \frac{\sigma(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1})}{\sigma(\epsilon_t) \sigma(\epsilon_{t-1})} = \rho\]

- \[\rho(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-s}) = \frac{\sigma(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1})}{\sigma(\epsilon_t) \sigma(\epsilon_{t-1})} = \rho^s\]

- \(\rho=0\) implies that the error terms are uncorrelated.

Proof Note that \(\epsilon_t = \rho \epsilon_{t-1} + u_t = \rho^2 \epsilon_{t-2} + \rho u_{t-1} + u_t\) > \(= \rho^3 \epsilon_{t-3} + \rho^2 u_{t-2} + \rho u_{t-1} + u_t = \cdots =\) \(\sum_{s=0}^\infty \rho^s u_{t-s}\).

(2) Since \(u_t\)’s are uncorrelated to each other and \(\sigma^2(u_t) = \sigma^2\), \(\sigma^2(\epsilon_t) = \sum_{s=0}^\infty \rho^{2s} \sigma^2(u_{t-s}) = \sigma^2 \sum_{s=0}^\infty \rho^{2s} = \sigma^2 \frac{1}{1-\rho^2}\) (\(|\rho|<1\)).

(3) Since \(E(\epsilon_t) = 0\), \(\sigma(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1}) = E(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1})\) > \(=E[(u_t + \rho u_{t-1} + \rho^2 u_{t-2} + \cdots )(u_{t-1} + \rho u_{t-2} + \rho^2 u_{t-3} + \cdots ) ]\) > \(=E[u_t + \rho (u_{t-1} + \rho u_{t-2} + \cdots )(u_{t-1} + \rho u_{t-2} + \rho^2 u_{t-3} + \cdots ) ]\) > \(= E[u_t (u_{t-1} + \rho u_{t-2} + \cdots )] + \rho E [ u_{t-1} + \rho u_{t-2} + \cdots ]^2\). By independency of \(u_t\), \(E(u_t u_{t-s}) E(u_t) E(u_{t-s})= 0 ~\forall s \neq 0\). \(\Rightarrow \sigma(\epsilon_t, \epsilon_{t-1}) = \rho E [ u_{t-1} + \rho u_{t-2} + \cdots ]^2 = \rho \sigma^2(\epsilon_{t-1}) = \rho \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2}\).

\(n \times n\) variance-covariance matrix of error \(\sigma^2(\epsilon)\) is given as \([ \kappa, \kappa \rho, \kappa \rho^2, \cdots, \kappa \rho^{n-1} ; \kappa \rho, \kappa, \kappa \rho, \cdots, \kappa \rho^{n-2} ; \vdots ; \kappa \rho^{n-1}, \kappa \rho^{n-2}, \kappa \rho^{n-3}, \cdots, \kappa ]\) where \(\kappa = \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2}\).

2. Durbin-Watson test for autocorrelation

Now, we want to determine if the regression model has autocorrelation or not. Note that \(\rho=0\) implies \(\epsilon_t = u_t\) ; uncorrelated.

\(H_0 : \rho=0\) \(H_1 : \rho>0\) (we consider the positive autocorrelation.)

Test statistic

\[D = \frac{\sum_{t=2}^n (e_t - e_{t-1})^2}{\sum_{t=1}^n e_t^2}\]where \(e_t = Y_t - \hat{Y_t}\).

Exact critical values are difficult to obtain, but there is an upperbound \(d_u\) and lowerbound \(d_l\) such that \(D\) outside these bounds leads to a definite decision. Decision rule:

- If \(D > d_u\), conclude \(H_0\).

- If \(D <\), conclude \(H_1\).

- If \(d_l < D < d_u\), inconclusive.

idea: Since \((\epsilon_t - \epsilon_{t-1})^2\) is small when the errors are positively autocorrelated, small \(D\) implies \(\rho >0\).

3. Remedial measures for autocorrelation

addition of predictor variables

Time-ordered effects are often due to the missing key variables. When the long-term persistent effects cannot be captured by one or several predictor variables, a trend component can be added to the regression model, such as a linear/exponential trend, or indicator variables for seasonal effects.

use of transformed variables

When it failed to cure autocorrelation from addition of predictor variables, we may consider transforming variables to obtain an ordinary regression model. It can be done by \(Y_t^\prime = Y_t - \rho Y_{t-1}\)

\[\Rightarrow Y_t^\prime = (\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_t + \epsilon_t) - \rho (\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{t-1} + \epsilon_{t-1}) = \beta_0 (1 - \rho) + \beta_1 (X_t - \rho X_{t-1}) + u_t\]Set \(X_t^\prime = X_t - \rho X_{t-1}\), \(\beta_0^\prime = \beta_0 (1 - \rho)\), and \(\beta_1^\prime = \beta_1\). \(\Rightarrow\) \(Y_t^\prime = \beta_0^\prime + \beta_1^\prime X_t^\prime + u_t\) where \(u_t\)’s are uncorrelated and follows \(N(0,\sigma^2)\).

To use the transformed model, we need to estimate \(\rho\). Let’s say that we have \(r\), an estimator of \(\rho\). Then, from the original fitted function \(\hat{Y} = b_0 + b_1 X\), we can restore \(b_0 = \frac{b_0^\prime}{1-r}\), and \(b_1 = b_1^\prime\) where \(s(b_0) = \frac{s(b_0^\prime)}{1-r}\), and \(s(b_1) = s(b_1^\prime)\).

There are three different procedures to obtain transformed models.

way 1: Cochrane-Orcutt procedure

It consists of three steps and their iterations. Each step is:

- Estimate \(\rho\).

Consider a regression function through the origin: \(\epsilon_t = \rho \epsilon_{t-1} + u_t\) where \(u_t\) is a random disturbance term. Since \(\epsilon_t\) and \(\epsilon_{t-1}\) are unknown, we use \(e_t\) and \(e_{t-1}\), instead. The estimator of the slope \(r\) is \(r = \frac{\sum_{t=2}^n e_{t-1}e_t}{\sum_{t=2}^n e_{t-1}^2}\) - Fit a transformed model. \(Y_t^\prime = \beta_0^\prime + \beta_1^\prime X_t^\prime + u_t\)

- Test for autocorrelation. By Durbin-Watson’s test

Note This approach does not always work properly. When the error terms are positively autocorrelated, the estimate \(r\) tends to underestimate \(\rho\).

way 2: Hildreth-Lu procedure

This is analogous to the Box-Cox procedure. The value of \(\rho\) is chosen to minimize the error sum of squres for the transformed regression model. \(SSE = \sum_t (Y_t^\prime - \hat{Y_t^\prime})^2 = \sum_t (Y_t^\prime - b_0^\prime - b_1^\prime X_t^\prime)^2\) Then test for autocorrelation (By Durbin-Watson’s test).

Note This approach does not need iterations. But optimization process is required.

way 3: first difference procedure

Facts

- The autocorrelation parameter \(\rho\) is frequently large (close to 1).

- \(SSE(\rho)\) is often quite flat for large values of \(\rho\). (When using optimization approach (way 2: Hildreth-Lu procedure).

Therefore, take \(\rho = 1\). Then, \(\beta_0^\prime = \beta_0 (1-\rho) = 0\) and the transformed model is \(Y_t^\prime = \beta_1^\prime X_t^\prime + u_t\) where \(Y_t^\prime = Y_t - \rho Y_{t-1}\), and \(X_t^\prime = X_t - \rho X_{t-1}\). In the transformed model, the intercept term is canceled out.

The fitted regression line in the transformed variables is \(\hat{Y^\prime} = b_1^\prime X^\prime\) which can be transformed back to the original variables as \(\hat{Y} = b_0 + b_1 X\) where \(b_0 = \bar{Y} - b_1^\prime \bar{X}\), and \(b_1 = b_1^\prime\).

Note This approach is effective in a variety of applications and much simpler than other 2 procedures. (The estimation process of \(\rho\) is deleted.)

4. forecasting with autocorrelated error terms

\(Y_t = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_t + \epsilon_t\) where \(\epsilon_t = \rho \epsilon_{t-1} + u_t\). i.e. \(Y_t =\)\(\beta*0 + \beta_1 X_t\) \(+\) \(\rho \epsilon*{t-1}\) \(+\) **\(u_t\)**.

Thus, the forecast for the next period \(t+1\), \(F_{t+1}\) is constructed by handling the three components:

- Given \(X_{t+1}\), estimate \(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_t\) from the fitted regression function \(\hat{Y_{t+1}} = b_0 + b_1 X_{t+1}\).

- \(\rho\) is estimated by \(r\) and \(\epsilon_t\) is estimated by \(e_t\). i.e. \(e_t = Y_t - (b_0 + b_1 X_t) = Y_t - \hat{Y_t}\). Thus, \(\rho \epsilon_t\) is estiamted by \(re_t\).

- The disturbance term \(u_{t+1}\) has expected value zero and is independent of earlier information. Therefore \(E(u_{t+1}) = 0\).

\(\Rightarrow\) The forecast for the period \(t+1\) is \(F_{t+1} = \hat{Y_{t+1}} + re_t\).

An approximate \(1-\alpha\) prediction interval for \(Y_{t+1, new}\) is obtained by employing the usual prediction limits for a new observation but based on the transformed observation. The process is \((X_i, Y_i) \rightarrow (X_i^\prime, Y_i^\prime) \rightarrow s^2(pred)\)

Therefore, an approximate \(1-\alpha\) prediction interval for \(Y_{t+1, new}\) is \(F_{t+1} \pm t(1-\alpha/2 ; n-3) s(pred)\) Here, the degree of freedom is \(t-3\) because only \(t-1\) transformed cases are used, and 2 degrees are lost for estimating the parameters \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\).

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: